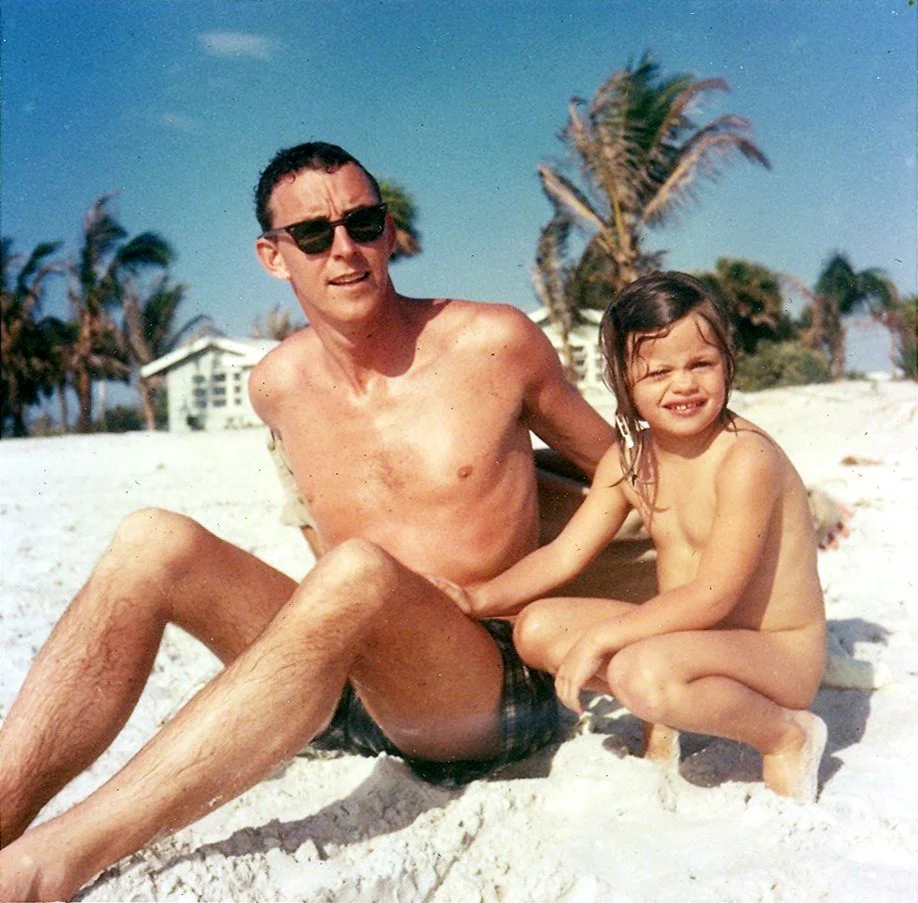

I did announce many times that I would never “be a writer.” No, no —not me—not ever. What a life. So static, so stuffy, so invisible. I wanted to be a singer. I’d think of my father’s worn corduroys, his hole-y sweater, his dogged routine of granola, giant mug of coffee in the kitchen, then going out to his studio in the orchard by about 7:30 every morning and staying there all day except for about one half hour for lunch. Then working into the night on correspondence, sometimes in front of the teeny TV in the living room, sometimes in a small study he had upstairs. I saw it as a sort of self determined plod, not having yet grasped the reasons. Having not yet understood. Why would anyone do this to themselves?

It took a lot of years to figure out why. But I have observed that for late bloomers, as they transition to full fledged adulthood, parents must be rejected or encountered and given a grade of some kind, and sometimes all three. I did this, to begin with, by reading.

I read his work, over and over again, and I found shifting meanings. Not shifting in what he intended the narrative to be, but shifting in terms of how I responded to it. This is a hallmark of good writing—you read the same book at different periods of your life and find new gems. This was absolute magic to me. Could I pull off anything like it? After all, I had always kept a journal. And I read copiously. And so, because I was the one who read a lot, we talked words, my father and I.

When we were kids he’d bring us little puzzles. For example he’d ask what is the difference between “complicated” and “complex,” or between “elucidate” and “explain.” I’d give my answers, which he seemed to find interesting. Later on, we’d talk about books. I went through a Dickens phase, a James phase, a Muriel Spark phase, and many, many others. I liked a wide range. Don DeLillo, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Styron, Updike, and on and on. I went to a Paris Review Revel with him and met Zadie Smith. Her book White Teeth changed my life, in terms of what was possible on the page. All of these books and writers sparked something in him and in me. He was wasn’t often a faker about things that mattered, and this really mattered. Without me realizing it, and in the sneakiest way, he was engendering and nurturing my love of words, the joy I had in the ability to precisely articulate something.

By my mid twenties the singing hadn’t panned out, so I tried investment banking, which was a complete bust. I then worked for a trade press in Manhattan. After three months I realized I was unhappy in a corporate environment. From fifty-two stories up it was not possible to open a window, though Central Park in springtime spread out far below like a moving tapestry. I dyed my hair black and quit.

Eventually I did exactly what I said I’d never do—I began to write. I did all kinds of jobs, cater-waitressing, baking, cooking, retail, and bookstores to support myself and leave my time flexible enough for a daily writing practice. Once I began, I got the “writing bug,” as my father called it, with a bemused expression on his face. From there we went on “talking shop,” he’d say. It was a struggle for me, and I’d labor long at a paragraph. He gave me all kinds of insights. “It takes as long as it takes,” was one. Another was, “Most writers have to write, there isn’t an alternative.” Another one, “The writing life is like a bowl of honey, you just have to lick it off a thorn.”

In 2012 I heard about the heist in Rotterdam, where the painting by Lucian Freud called Woman with Eyes Closed was stolen along with several old masters works. I was captivated with the story; I followed every development on the news. I thought I might have a novel in it. I expounded on the facts, and had the stolen paintings migrate to the town I grew up in. I created the character of abstract expressionist painter George Clayton based on my father, the best of him. George sees talent in his daughter Perrin, who will later make an attempt to rescue the missing paintings. George is not particularly materialistic, and gives her and her husband Jack a multi-million dollar piece of oceanfront land as a wedding present. He doesn’t want to be meddlesome, but he finds ways to encourage his daughter. Though—like most artists, he is primarily interested in whatever he's working on. He’s charming in an old world way. He has a rumpled linen suit, blue, that he breaks out for special occasions. He almost always has fishing lures in his pocket. He rarely swears. He has an excellent, if dark, sense of humor. When the weather allows, he rides to the ocean every day at about five o’clock for a dip. He works constantly, and is happiest at work on a project that’s going well. He hardly ever takes a day off. In his studio he wears a sweater with holes in it and worn out corduroys, and doesn’t notice at all.

Well, he was right about the writing life. It was and is tough. After he died I missed those talks very much. It was strengthening to know that even someone as successful as he was still struggled at times, and in fact, often.

Back to the grading that has to happen, for the late bloomers or even the very late bloomer. Regarding the parents. After some time I began to understand what he was doing, waking early, getting the granola and the coffee, and going out to his studio, wishing to be undisturbed. Of course he wished it—he had a whole world in the books he was writing. A world created by him. And I did eventually figure out that he was having fun out there. For the children of artists, that reckoning might be more intense, we don’t have as many trips and holidays and osmotic, shared experiences. We go through the work, we reflect on the work. We turn it round like a crystal, noticing how the light refracts on different days, and in our different moods. Paying attention to it is like a process of revision, and is, essentially, what we have of them.